When Kimberly Finke became principal of Albuquerque’s Whittier Elementary School in 2019, she brought with her a wealth of experience successfully turning around other struggling schools in Gallup and Albuquerque.

Whittier has been no different. Despite the enormous speed bump that is Covid-19, Whittier has made enormous progress under Finke’s leadership. When she arrived as a result of interventions required by New Mexico’s implementation of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), many Whittier students were two or more grade levels behind in reading. In the first couple of years, more than half of those students were on pace to catch up within another year. Then Covid hit with “devastating” effects, Finke said.

As the pandemic recedes, Whittier is picking up steam again, because the systems Finke established are strong and her staff now has experience in turning things around.

New Mexico Education interviewed Finke to learn her turnaround secrets, and to examine with her whether large-scale turnaround is possible, and, if so, what are the necessary elements of a successful turnaround strategy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

New Mexico Education: Let’s start with a bit about your background turning around schools before Whittier.

Kimberly Finke: I started my career in Gallup. I learned about school turnaround there by doing two school turnarounds. The first was Jefferson Elementary, where Wilhelmina Yazzie (a lead plaintiff in the Yazzie-Martinez education adequacy lawsuit) was one of my parents, and then at Gallup High.I came to Albuquerque Public Schools six years ago. I was at Corrales Elementary School for two short years, and we went from an F rating to a B in that time.

Then in 2019 the district asked me to come down to Whittier, because the state had come down and named three APS schools, including Whittier, as the worst schools in the state and they were threatening shutdown. We had to come up with plans to basically convince the state that our schools were worth keeping open.

I’m a big believer in neighborhood schools. I firmly believe that neighborhood schools are still the best option for most parents in public education. Not everybody has the ability to go out shopping for schools, there are transportation concerns, all that kind of thing. So I think we’re obligated to provide great neighborhood schools for our kids.

NME: What are the basic components of your turnaround strategy at Whittier?

Finke: The first one is an extended school year. We extended the school year by 10 days as part of the turnaround. [This was before the Extended Learning Time Program was created and funded for every school that wants to participate, and perhaps it even inspired it.] We pushed for the program so we could get consistent funding for it. My teachers know there are 10 extra days on the contract.

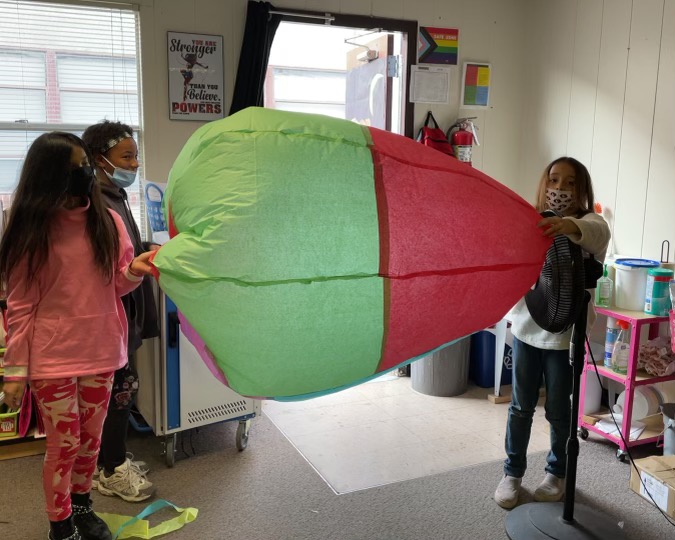

We also extended the school day. So my kids get an extra 45 minutes of school each day. And instead of having that be more interventions, we have something called Genius Hour. It’s enrichment.

Why do we do this? Well, if you grow up in my household, I have the means to provide horseback riding lessons or swimming lessons or coding or tutoring or whatever I need to for my kids. It’s just part of being a middle class family. But a lot of our families can’t provide that for their kids. So we do it here at school.

The last 45 minutes of the day, they get basketball or archery or cooking class or comics, drama, string art, ukulele, sign language. The kids come up with the ideas. They particularly love the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) offerings. We have different rotations so they get to try out four or five new things a year.

And they all tie somehow into academics as well. With chess, there are aspects of math and coding. When I’m learning to cook, I’m actually applying my fractions. And there are huge social-emotional aspects of having that enrichment as well.

These are the experiences that we want to make sure every kid gets. We feel it’s an equity issue. Because those are the types of experiences that really make learning meaningful.

Teachers have a longer day as well. They work an eight-and-a-half hour day here (compared to the standard 6.5 hour contract utilized by most APS schools). We have professional development every morning. We’ll learn about something one day, and then we have a chance to go practice it. We sit down and write plans, and set up centers where teachers can come for help. I describe it as job-embedded professional development.

In education, so often it’s just drive-by professional development. Teachers have that feeling well, if I just had time to put that together. That would be such a cool thing to do. So we have the time to put it together. We learn about it. And then we do it.

NME: How have you worked with the teachers union to get them to go along with these longer days and years?

Finke: The union had an interest in not seeing a neighborhood school get shut down. So they showed a really high degree of flexibility in allowing us to negotiate those things for teachers. The union has really backed trying to get legislation written to allow these programs to be adopted by other schools.

Finke: The union had an interest in not seeing a neighborhood school get shut down. So they showed a really high degree of flexibility in allowing us to negotiate those things for teachers. The union has really backed trying to get legislation written to allow these programs to be adopted by other schools.

NME: Do your teachers get extra pay for the additional days and hours they put in?

Finke: They do get about a $13,000 bump in pay. But I’m not gonna lie. It’s hard. It’s not like people are just getting handed all this extra cash. They work very hard.

NME: How would you describe the neighborhood and conditions where Whittier is located?

Finke: Based on the 2010 census, this neighborhood has the highest rates of child poverty and food insecurity in New Mexico. Our children are far more likely to be raised by mothers without a high school diploma. They are more likely to be reported for child abuse or neglect, far more likely to be referred to the juvenile justice system. So it’s a neighborhood that needs more.

We have about 40 families right now on the verge of homelessness just because of what’s going on with the landlords and rents in this area. I have a family that just enrolled that was living in their car for a year but then their car got stolen, so now they’re doubling up with friends.

NME: How would you say all of this is reflected in academic challenges facing these kids?

Finke: The first year I was here, we dug through data. New Mexico tracks cohorts of kids, and what I learned was that only 48 percent of Whittier kids graduate on time from high school. So we are trying to turn that statistic by making sure that they’re going off to middle school with appropriate reading skills, that they can write, that they can do the mathematics they need to do to get through algebra, because that’s the gateway class for high school.

NME: As you dig out from the impacts of the pandemic, what gives you hope?

Finke: Before the pandemic, our kids were getting almost a year-and-a-half of growth in a year. The pandemic hit and it has been devastating. And I have to say online kindergarten is maybe the dumbest thing that has ever been thought up in the world.

But we can do it again. We know what to do. We’ve already done it once here. There’s not that sense of panic about it. Our collective attitude is OK, we’ve got this. We got this. We know how to talk to parents. We know how to involve them. We know how to set up interventions. None of these systems were in place when we started. There were no intervention systems. There were not even testing and assessment systems, So we didn’t really even know how our kids were doing. I’m a strong believer in data: you always have to go back to the data.

NME: Everything you say about how you’ve turned around schools makes so much sense, it begs the question: Why don’t more schools do it?

Finke: It takes more money, but even more important, it involves changing people’s belief systems. It’s getting people to change their mindsets and understand they’re our kids.If they’re going to have the same outcome as everybody else – they’re going to graduate, they’re going to go to college or the military or trade school – then they need more. They need more everything.

They need more time. They need more love. They need teachers with more experience and more training. They need more time on task, they need more enrichment. They just need more. And that’s okay. That’s absolutely OK.

NME: Does it take special teachers and a special leader to make this happen

Finke: I call it love the one you’re with. How do you work with the teachers? There’s a lot of teacher blaming. When a school is failing, it’s always “they’re bad teachers.” Well, guess what? We don’t have a lot of teachers. There was a giant shortage before and now it’s just epic. You have to love the one you’re with. You have to figure out how to develop who you have.