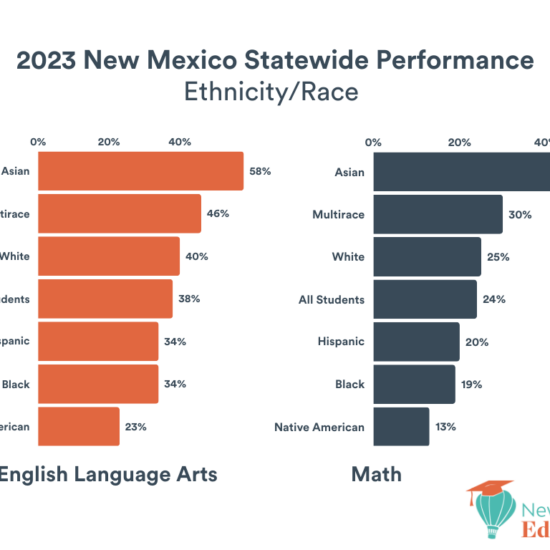

Significant discrepancies in proficiency rates between gold-standard national tests and New Mexico’s new state assessment suggest that New Mexico might have lowered the bar this year, masking just how far behind its students are, according to a national policy expert.

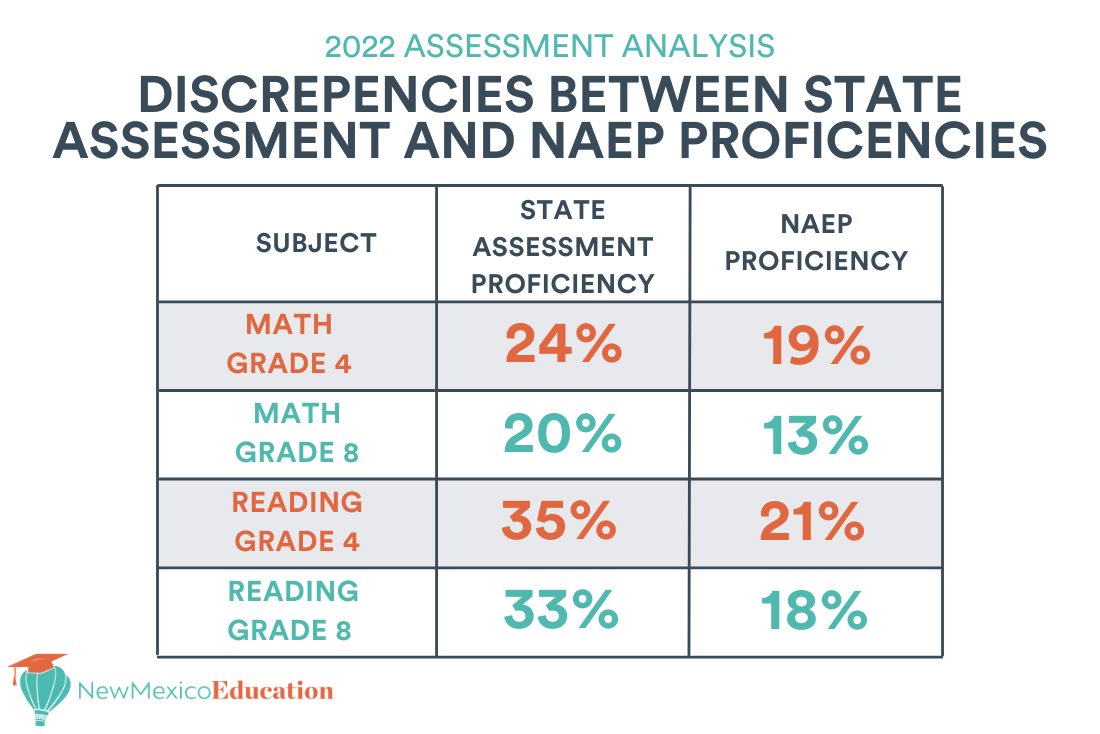

A review of 2022 results of fourth- and eighth-grade math and literacy tests (two grades the national test covers) from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) and New Mexico Measures of Student Success and Achievement (NM-MSSA) show higher proficiency rates on the state test than NAEP ranging from 5 to 15 percentage points. Gaps are higher on the reading tests than the math exams.

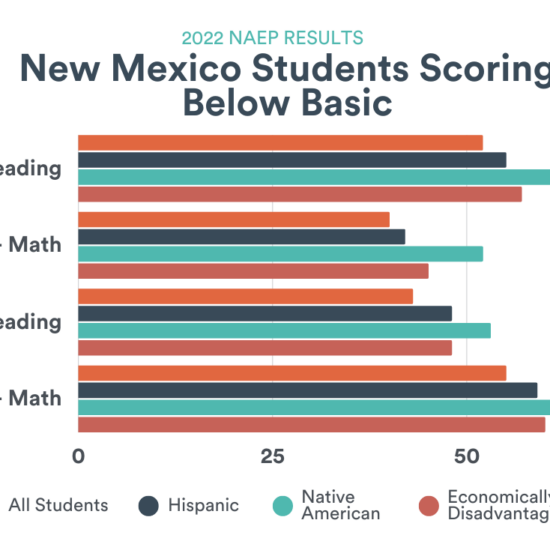

On NAEP, 21 percent of the state’s fourth-graders scored proficient or better in reading, while on NM-MSSA, 35 percent were proficient or better. On eighth-grade reading, 18 percent were proficient or better on NAEP, while 33 percent hit or exceeded that target on NM-MSSA.

Math gaps were a bit smaller. On NAEP, 19 percent of fourth-graders were proficient or better, compared to 24 percent on NM-MSSA. Just 13 percent of eighth-graders were proficient or better on NAEP math, while 20 percent were proficient on NM-MSSA.

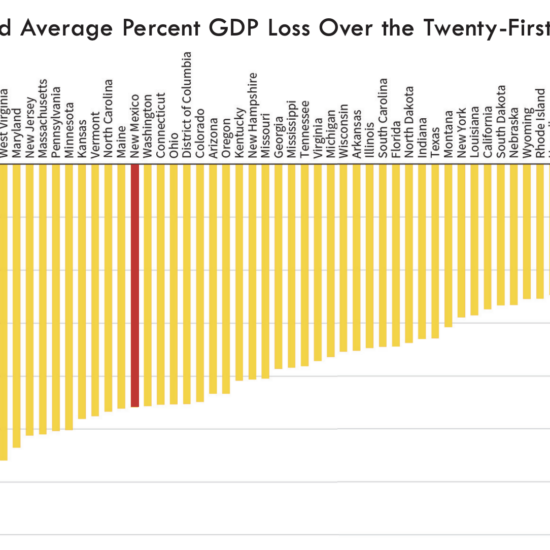

New Mexico students had the lowest scores on NAEP among the 50 states and Washington D.C., according to results released in late October.

While the two tests are very different from one another and no one should expect them to align perfectly, the consistent gaps suggest the state test lacks rigor and might not reveal whether New Mexico students are being prepared for a successful life after high school. That’s the view of Michael Petrilli, president of the conservative-leaning Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Petrilli has been writing about the so-called ‘honesty gap’ between state and national tests for at least seven years. The nonprofit Collaborative for Student Success defines the honesty gap as states exaggerating the proficiency rates of their students by setting rates lower than those established by NAEP.

In 2015, Petrilli wrote an article for Education Next magazine praising then-new state assessments proliferating across the country that were tied to Common Core State Standards. PARCC, which New Mexico jettisoned in 2019, was one of those tests,

While many states have stuck with those rigorous exams, New Mexico appears to be a troubling exception Petrilli said in an interview this week with New Mexico Education.

“State tests generally have remained relatively rigorous as compared to NAEP, so they are much closer to closing that honesty gap than they used to be,” Petrilli said. “And so the fact that New Mexico is now returning to the days of setting a much lower standard, that does make it an outlier.

“Of course, that’s the last thing you want to do when you find yourself in last place.”

There are reasons to view these results, and the discrepancies between them, with caution and avoid jumping to definitive conclusions, Petrilli said. “Last school year was still a weird year, with the Omicron variant and some disruptions and chaos still occurring,” he said. “So we might want to wait for two years from now (when NAEP is next administered) to see if the same patterns holds in New Mexico, or if we revert to normal. I think that’s unlikely, but it is possible.”

Petrilli floated another possible explanation for the discrepancy: NAEP was administered a couple of months earlier than the state test, and kids could potentially have learned a significant amount during that time. Again, he said he doubted it would account for such a big gap.

After decades of assessments that lacked rigor, when parents were given rosy but erroneous information about how well school was preparing their children for a successful life, states made progress in telling a truer story. Why would New Mexico want to go backwards? That’s a question Petrilli said state policymakers and officials should ask themselves.

“It’s important in terms of the message it sends to educators about what the goal is – what are you actually trying to achieve?” Petrilli said. “And of course it’s important in terms of the message it sends to kids and to parents.

“States have a responsibility to at least try to communicate to parents the truth about whether kids are on track for success or not.”